Free stuff from 3dtotal

This is where you can find and download from our growing library of free stuff! You can use this to get an idea of what you'll find in our printed books, access eBooks, out-of-print books and magazines, or, if you're a new artist looking for some tips and tricks, then we hope you'll find the content here a good place to start!

Latest free stuff

-

Click through to download

GRAPHITE issue 02 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

GRAPHITE Issue 01 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Digital Art Masters: Volume 9 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per

All of our free offerings

Filter by interest:

-

Click through to download

Anatomy for Artists - SAMPLE (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Anatomy for Character Design (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

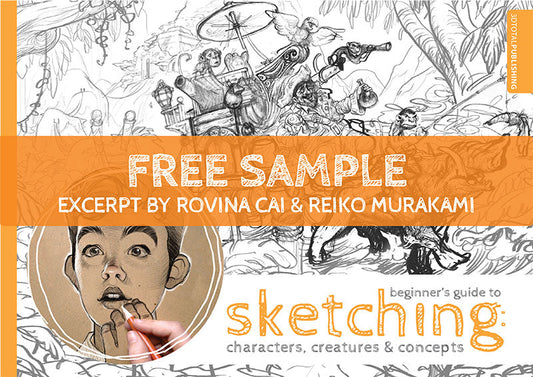

Beginner's Guide to Sketching - FREE CHAPTER 01 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Beginner's Guide to Sketching - FREE CHAPTER 02 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Beginner's Guide to Sketching - FREE CHAPTER 03 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Beginner's Guide to Sketching - FREE CHAPTER 04 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Beginner's Guide to Sketching - FREE CHAPTER 05 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Beginner's Guide to Sketching - FREE CHAPTER 06 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Character Design Quarterly - Sample Issue 2019 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Character Design Quarterly - Sample Issue 2021 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Character Design Quarterly - Sample Issue 2023 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

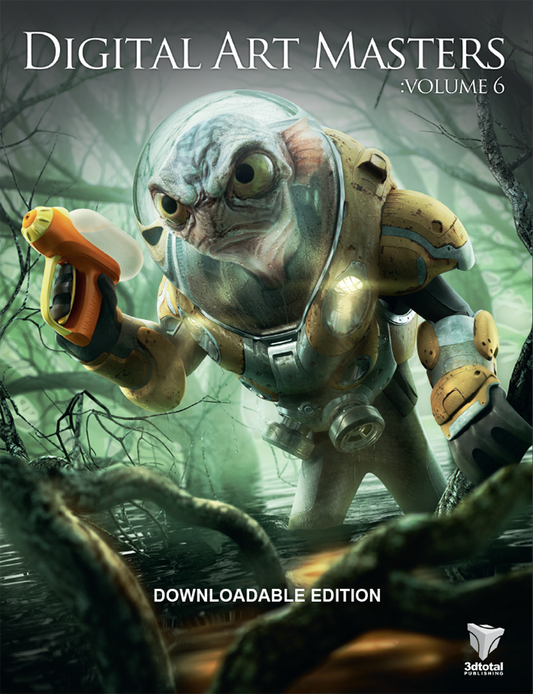

Digital Art Masters: Volume 6 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

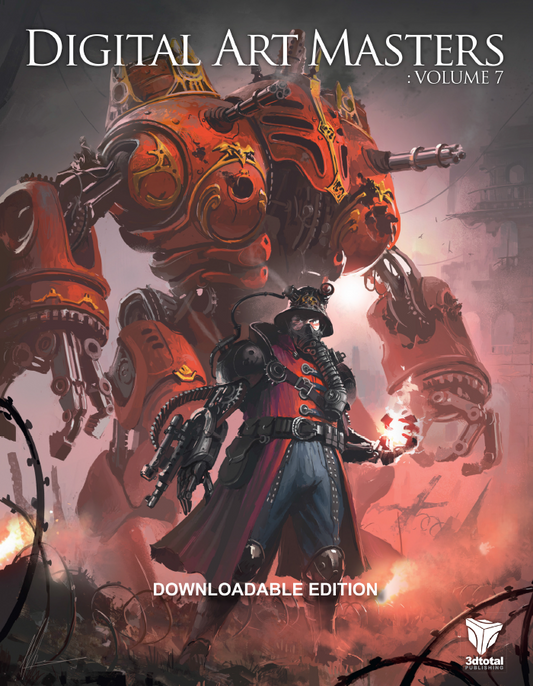

Digital Art Masters: Volume 7 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Digital Art Masters: Volume 8 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per£0.00 GBPSale price Free! -

Click through to download

Digital Art Masters: Volume 9 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

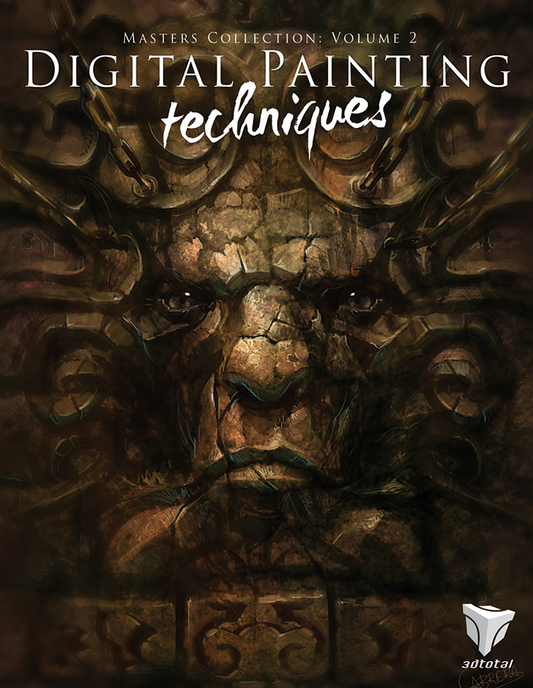

Digital Painting Techniques: Volume 2 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per£0.00 GBPSale price Free! -

Click through to download

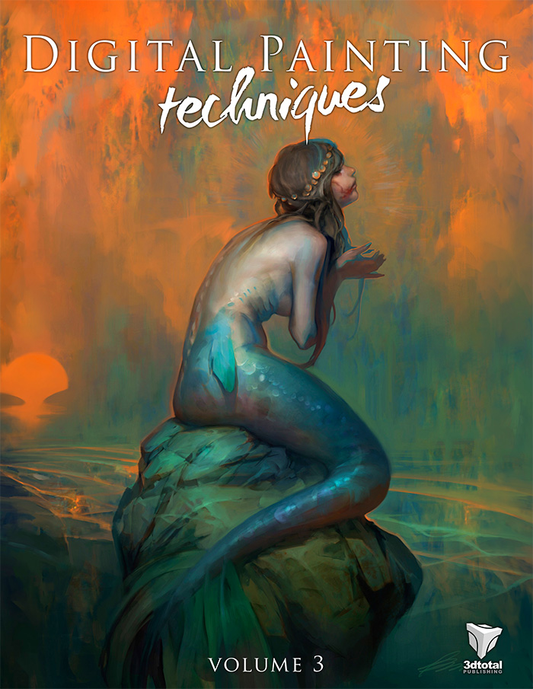

Digital Painting Techniques: Volume 3 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per£0.00 GBPSale price Free! -

Click through to download

Digital Painting Techniques: Volume 4 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

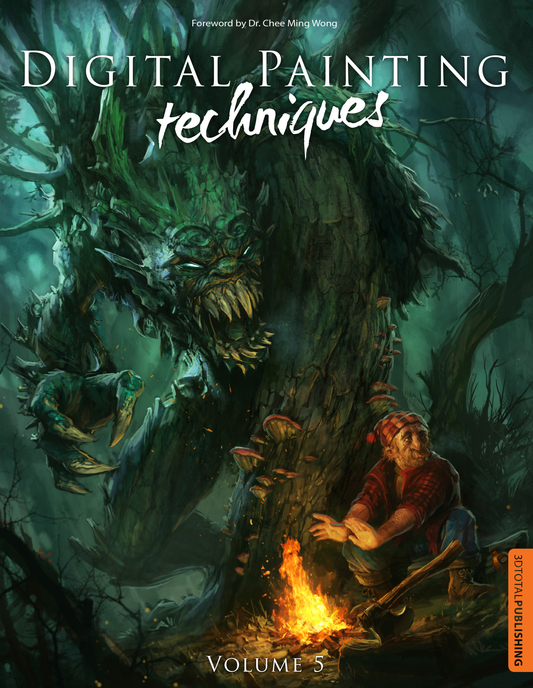

Digital Painting Techniques: Volume 5 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Digital Painting Techniques: Volume 6 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Digital Painting Techniques: Volume 7 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Digital Painting Techniques: Volume 8 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per£0.00 GBPSale price Free! -

Click through to download

FREE CHAPTER - Beginner's Guide to Sketching: Robots, Vehicles & Sci-fi Concepts (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

FREE CHAPTER - Creating Stylized Characters (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

FREE ISSUE - 2DArtist: Issue 116 - August 2015 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

FREE ISSUE - 2DArtist: Issue 136 - April 2017 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

FREE ISSUE - 3DCreative: Issue 120 - August 2015 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

FREE ISSUE - 3DCreative: Issue 125 - January 2016 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

FREE MAGAZINE - Total Issue 01 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

FREE MAGAZINE - Total Issue 02 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

FREE MAGAZINE - Total Issue 03 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

FREE MAGAZINE - Total Issue 04 (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

GRAPHITE Issue 01 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

GRAPHITE issue 02 (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Handy hints: a compilation of tips on drawing hands (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

How to Be a Children’s Book Illustrator - SAMPLE (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Loish - Coloring Book (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Masters of Sketching: Abigail Larson & Christina Mrozik (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Masters of Sketching: Jim Pavelec & Bobby Rebholz (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Masters of Sketching: Patrick Ballesteros & Paride Bertolin (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Sketch Workshop: Characters (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per£0.00 GBPSale price Free! -

Click through to download

Sketch Workshop: Cityscapes (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Sketch Workshop: Creatures (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Sketch Workshop: Landscapes (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per£0.00 GBPSale price Free! -

Click through to download

Sketch Workshop: Robots & Spaceships (Downloadable Edition)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per£0.00 GBPSale price Free! -

Click through to download

Sketching from the Imagination: Dark Arts 8-chapter sample (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per -

Click through to download

Total Textures 19-pack Download Bundle (Download Only)

Regular price Free!Regular priceUnit price per£0.00 GBPSale price Free!